Photo by Juxy2 – This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Starting the Sixth year of this blog – somewhat late – I found some inspiration to start writing here again, courtesy of to my sister who posted a note on Facebook about apparitions and hauntings at Manchester Airport in the UK. It’s fascinating stuff, and I have an article about a couple of famous aviation events and their connection with spiritualism on the back burner. I thought to myself “I wonder what other airfields have a ghostly connection?” Since I’ve seen various “ghost hunter” documentaries some of which mentioned hantings and visitations at historic airfields and bases. Some of the stories including the two or three related here have been repeated across websites and bulletin boards so many times that any factual basis has been seriously mangled. However, one or two hauntings can be cross-referenced with well documented accidents at British airports.

Croydon – 1936

Despire a perception of being a fairly prosaic place, “Haunted Croydon” is quite a popular Google search. If you’re an aviation history buff you’ll be thinking of something very specific. Wikipedia says Croydon Airport was the UK’s only international airport during the interwar period. It opened in 1920 and (unsurprisingly since it was the only international airport) handled more cargo, mail, and passengers than any other UK airport at the time. Innovations at the site included the world’s first air traffic control and the first airport terminal. In 1943 RAF Transport Command was founded there. The airport closed in 1959. In 1978, the terminal building and Gate Lodge were granted protection as Grade II listed buildings In May 2017 the Gate Lodge was classified as “Heritage at Risk” by Historic England.

On 9 December 1936, a KLM Douglas DC-2 registered PH-AKL and named Lijster crashed shortly after taking off from Croydon in foggy conditions on a scheduled flight to Amsterdam. According to common practice in bad weather, the DC-2 started its takeoff run following a white line painted on Croydon’s grass landing area, but veered to the left and headed south towards rising ground instead of the normal westerly direction. The aircraft hit the chimney of a house in Purley and crashed into an empty house on the opposite side of the street. Two (mercifully empty) houses and the DC-2 were destroyed by the crash and ensuing fire. 14 passengers and crew were killed. Notable passengers who perished were Arvid Lindman, a former Prime Minister of Sweden, and someone familiar to aviation buffs, Juan de la Cierva, the Spanish inventor of the autogiro. A flight attendant and radio operator survived. The official investigation into the accident was ended on 16 December 1936 without reaching a verdict.

Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives

Until its closure, Croydon airport was said to be haunted by the ghost of the unfortunate Dutch pilot who walked around the surrounding area, warning people of the fog. A 2008 article in a local newspaper said that a fortnight after the crash another pilot was plotting his course when a voice behind him said: “You can’t take off, the weather is just the same as when I did.” The pilot turned to see a figure of the dead pilot standing behind him.

There are several variations of this story – another tale recounts a female aviator in the 1950s seeing a pilot in old flying gear illuminated by a lightning flash.

Croydon – 1947

11 years after the crash of PH-AKL, an accident with several twists and a supernatural postscript occurred on 25 January 1947. A C-47A Skytrain, (aka Dakota) belonging to Spencer Airways (owned and flown by Edward Spencer) failed to get airborne from Croydon on a flight to Salisbury, Rhodesia via Rome. 11 passengers and one crew member – Edward Spencer himself – were killed. 11 people survived, seven of whom were taken to Croydon General Hospital although only two were detained.

The Spencer Airways aircraft was an ex-USAAF C-47A-85-DL construction number 19979 originally with the AAF Serial 43-15513. Evidence from the American Air Museum in Britain suggests that 43-15513 may have served with the 44th Troop Carrier Squadron, 316th Troop Carrier Group, 9th Air Force USAAF based at RAF Cottesmore, UK. Subsequent civil registrations for this aircraft were NC32975 and VP-YFD. On a side note I don’t see this aircraft listed in Joe Baugher’s website so I ought to email him.

It was cloudy and snowing when the aircraft took off shortly before noon. The starboard wing was seen to drop, then the aircraft turned to the left and the port wing dropped. The pilot apparently applied full starboard aileron but the bank angle increased to 40 degrees with the port wing tip only a few feet from the ground. As it reached the perimeter track, the aircraft levelled out and swung to the right. It then stalled, impacted the ground and crashed head-on into a parked C-47 OK-WDB belonging to Czech airline CSA. Both aircraft caught fire, and were subsequently destroyed. Two or three mechanics carrying out an inspection on the Czech C-47 escaped with minor injuries.

The British Ministry of Civil Aviation investigated, and found that Spencer’s aircraft did not have a British Certificate of Airworthiness, nor a valid Certificate of Safety. None of the crew held a Navigators license nor a license to sign a Certificate of Safety

The Chief Inspector of Accidents opened a Public Inquiry on 24 February 1947. The co-pilot gave evidence that the aircraft had just been delivered from the United States following purchase by Spencer. It had been ferried to Croydon the day before the accident. The long-range fuel tanks used for the ferry flight had been removed and the passenger seats fitted. Preparing the aircraft had taken all day and night and Spencer was said to have had only two hours’ sleep.

A witness gave evidence that the wings of the C-47 were covered in snow, and that he had not seen any attempt to defrost the aircraft before takeoff. Another witness stated that Spencer did not smoke or drink and had many hours flying experience since the early 1930s. Counsel representing the next-of-kin of Captain Spencer made a formal protest that they had not been able to question the statement about Spencer’s lack of sleep. The inquiry was closed on 28 February following technical evidence. An aircraft engineer stated that the starboard engine had been in “a bad state” and was “popping and spluttering” before the aircraft had taken off. The accident was determined to be the result of loss of control by the pilot while attempting to take-off in a heavily loaded aircraft in poor visibility, and “an error of flying technique by a pilot who lacked Dakota experience” Other factors may have been snow and frost on the wings and pilot fatigue.

Among the dead were Mother superior Eugene Jousselot and sisters Helen Lester and Eugene Martin of the Congregation des Filles de la Sagasse (Daughters of Wisdom – a Catholic religious institute of women founded in 1707) who were travelling to Nyasaland (today part of Malawi). A contemporary newspaper report suggested that the nuns held South African passports.

The ghosts of the three nuns were reported walking around the Roundshaw estate in the mid-1970’s. Roundshaw was built on the site of the first Croydon Aerodrome (originally named ‘Plough Lane’) which was demolished in 1928. It is alleged that on one occasion a nun was seen in the bedroom of a new house and was said to have told a little boy a bedtime story. In 1976 a woman on the estate was so distressed at the sight of a nun in her living room that she asked the council to transfer her to another house.

Hounslow

Heathrow Airport

I can imagine that somewhere as busy as Heathrow might cause a certain degree of paranormal activity simply because of the number of individuals passing through it in normal operation. One of Heathrow’s ghosts, however, is from another era and seems to have adapted to new surroundings.

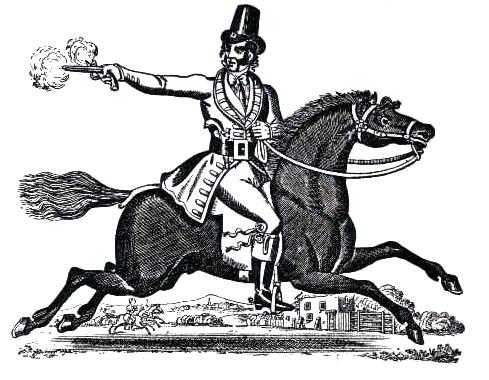

The Ghost of Dick Turpin (1705 – 1739)

Dick Turpin? Heathrow Airport? Apparently so. Ghost hunting sights have reported people seeing, hearing, feeling, and in one case, being attacked by the ghost of Dick Turpin at Heathrow. What is now the A4 from London to Bath ran through a locality known at the time as Heath Row. During his career as a highwayman, it is said that Turpin would lurk in the area around Heath Row before holding up coaches on the lucrative London-Bath route. More than 200 years after his execution in York, unfortunate people are supposed to feel warm breath on their neck, and hear strange sounds (barking and yelping of human origin) close by. A ghostly man in a tricorn hat wanders around Heathrow. The trouble is that when I think of people in tricorn hats in Heathrow saying “Stand and Deliver” I’m more inclined to think of 80s icon Adam Ant, or the exorbitant prices charged in the restaurants. As for people standing behind you and breathing down your neck – at Heathrow that wasn’t exactly unusual when I was there.

The Man with the Briefcase

Heathrow’s first major accident happened at 9.14pm on March 2, 1948, when a Douglas DC-3C registration OO-AWH of the Belgian airline Sabena crashed just short of Runway 28R in low visibility while carrying out a Ground Controlled Approach. Of the 22 people on board, 20 were killed.

DC-3C was the catch-all designation for ex-military C-47, C-53, and R4D aircraft rebuilt by Douglas Aircraft at its Santa Monica plant in 1946. These aircraft were given new manufacturer erial numbers, (MSN) and sold on the civil market. 28 new aircraft, completed by Douglas in 1946 with unused components from the cancelled USAAF C-117 production line were given the designation DC-3D. Some commentators mention aircraft that were “built but never delivered to the US Air Force” [sic]

OO-AWH was DC-3C with MSN 43154, and reportedly the last DC-3C refurbished at Santa Monica. Its prior history is a little interesting. It seems to have been built as a C-47A-5-DK (MSN 12276) by Douglas at Oklahoma City and given the AAF serial 42-92472. Joe Baugher’s notes say it went to the RAF as FZ679. Joe further notes: “Engine cut on takeoff, aircraft swung off runway and DBR (damaged beyond repair) when it struck an unidentified B-26 at Lyon-Bron Feb 15, 1945. May have been rebuilt and returned to service. There is a report that it rebuilt by Douglas at Santa Monica as DC-3C MSN 43154 and delivered Apr 9, 1947 to Sabena as OO-AWH”.

“May have been rebuilt” is the key here. It seems more likely to me that a structurally intact C-47 saw the light of day again as a DC-3C rather than a basket case of spare parts that had been written off in France two years earlier. However many websites and reports give a garbled history of the aircraft, mixing the type histories of the DC-3C and -3D together.

Photo by RuthAS This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

The official narrative of the crash says that the DC-3C’s approach to London-Heathrow Airport was started in reduced visibility. On final, the aircraft hit the ground, exploded and came to rest in flames short of the runway threshold. The pilot had continued the approach below the minimum safe altitude and was unable to see the ground in night and fog. At the time of the accident, [horizontal] visibility was 200 yards.

Workers in a hangar nearby saw the aircraft crash on (or short of) the runway and went to assist. When they reached the aircraft there was utter devastation, only the tail section of the aircraft was left intact. Some badly burned survivors were pulled from the aircraft and sadly died later, but many perished in the wreckage.

Following the crash, the Ministry of Civil Aviation stipulated that ground-controlled approaches would no longer be available to aircraft landing in conditions of less than 150 feet vertical visibility and 800 yards horizontal visibility except in an emergency.

The most common versions of the story say that, as the rescuers worked, a man wearing a dark suit and hat approached them, asking if the team had found his briefcase. As the rescuers were staring at him, he disappeared into the fog – never to be seen again. It is further alleged that the emergency workers later reported finding the same man’s body in the wreckage. The legend of the Man with a Briefcase was born. Other ghost sites allege that he has been seen at different times around the runways at Heathrow and even inside its terminal buildings. Whether or not he’s the man in the suit who’s occasionally seen in the VIP lounge (but only from the waist down) is a matter of conjecture.

One incident which has been conveniently connected with the “Man with a Briefcase” occurred in 1970, when the airport radar office reported a person trespassing on a runway. Officers of the airport police and fire service searched for the intruder, but the police reported that they were unable to see anyone, and the runway was clear. The radar office apparently expressed their disbelief, telling the police officers that as they were arriving at the scene, they had driven right past the person in question. This apparition has been assumed to be another visitation by the Man with (or without) his Briefcase. I’ve watched several TV documentaries in which a police helicopter with a heat-seeking camera attempts to direct police officers to the location of a criminal in hiding, only to see them walk straight past. Driving straight past an individual hiding out on a dark airfield with the only guidance being “you’re right next to him” and missing that individual is not entirely unbelievable. However it always makes a good story better.

There are a number of aviation related hauntings which related to highly publicized crashes in the United States, and probably many more related to military sites around the world. I hope to cover some of those in another article.